Ren’s route started ordinary—warehouse dock, manifest stack, coffee gone too soon. He scanned the morning load and paused on a tube: heavy-duty cardboard cylinder with metal end caps and a tamper strip sealed clean. No return address, just a printed label: Deliver to: 13841 Vespera Rd and the loose instruction you see when someone’s not paying per word—time-sensitive.

He slotted the tube in a milk crate behind the passenger seat so it wouldn’t roll, strapped the rest, and pulled out into the pale heat. The sky over the valley had that bleached look that makes the world seem twice as far away. Traffic thinned as the suburbs gave up their cul-de-sacs to scrub and power lines. The navigation app drew its easy blue thread across his windshield and sounded sure of itself—until it wasn’t.

Recalculating.

He watched the line redraw, kink, then straighten again. A lane closure ahead. No problem. The detour sloped east, then north a little too far, then east again. Ren let it ride. The high desert is full of long rectangles of nothing that all rhyme with each other; you cut across where it tells you and trust you’ll land near the right edge.

Recalculating.

The phone blinked, then settled on a new course through roads named after saints and numbers. He saw fewer houses and more land between them. Joshua trees lifted their arms like tuning forks. At a junction where the asphalt changed shade and the sign had been shot twice in the zero of 40, he checked the tube again with a glance and touched the label like it was someone’s shoulder. Still there.

He took a right as instructed. After two miles the road narrowed to a two-lane and then forgot one of the lanes on a cracked ridge. The app kept its tone level, the way polite voices do when they’re wrong.

Recalculating. Turn left in 400 feet.

There was no left. A wash had eaten it years ago and a row of skinny pylons did the job of a shrug. Ren slowed, eased around the pylons onto hardpack that wore tire marks like rumors, and the van answered with a soft stutter as pebbles stung the undercarriage.

The signal bars on his screen dwindled, took a breath, and went away.

He could have doubled back. He should have doubled back. The back road, though—this path of everyone else’s bad decisions—kept pointing itself toward a notch in the ridgeline that felt like the right idea owned by the wrong afternoon. He took it and told himself he was watching the odometer, that he could undo this, that distance is just a number you can spend and then earn back later.

When the notch opened, a town appeared. That was the word the map would have used if the map had been participating: town. Low cinderblock buildings with their windows boarded, a water tower with its paint peeled to the skeleton letters of ED— something, a gas station with its pumps wrapped in clear plastic sunburned to beige. A wind had taught weeds to bow in one direction. Far off, a lone trailer sat like a thought someone had forgotten to finish.

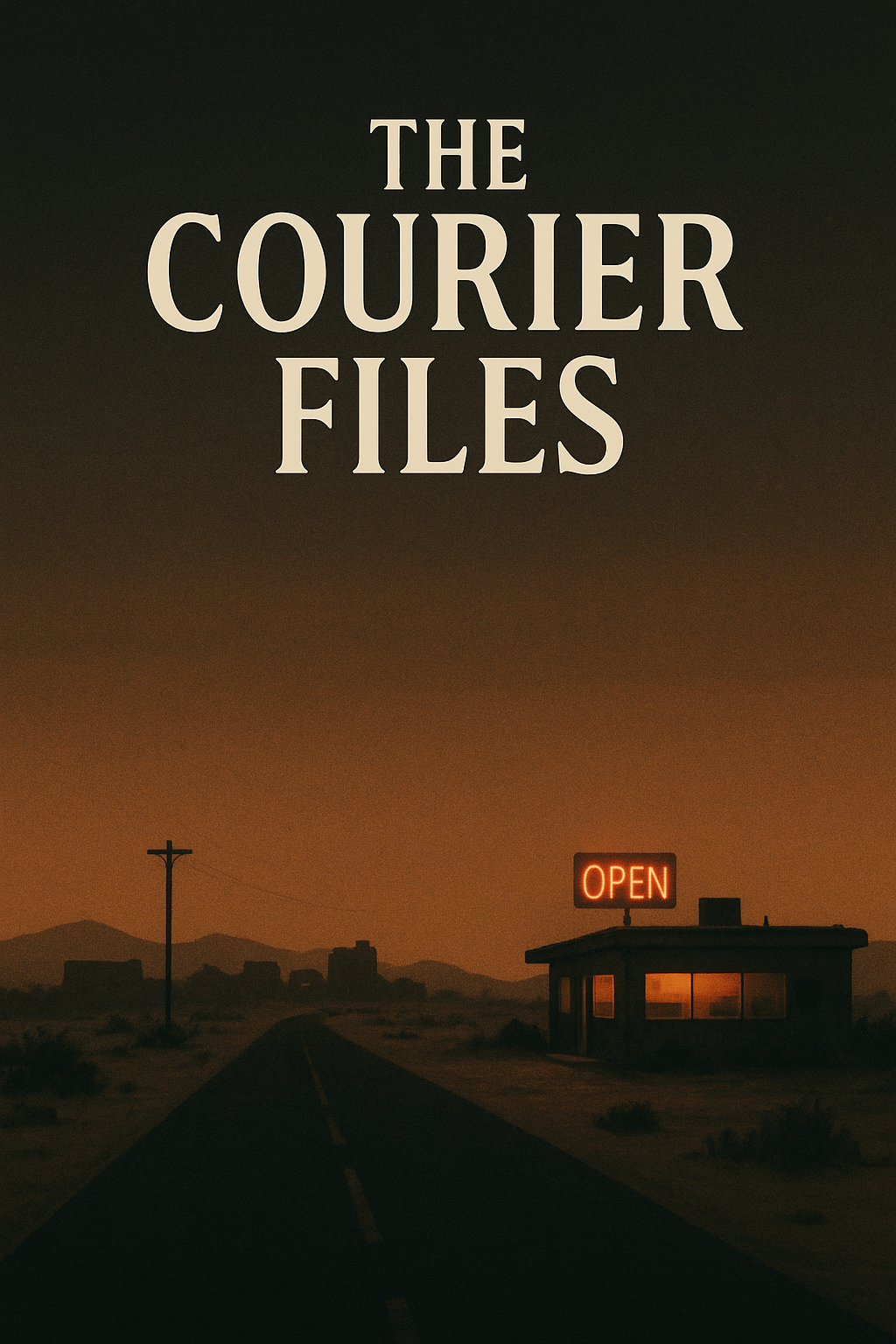

Ren coasted in and let the van idle. The town was quiet, but not abandoned the way photos are abandoned. It wore its quiet like a jacket it had chosen. Half a block down, a neon OPEN sign flickered in a diner window, its red script buzzing faintly even with the engine running. A slice of bright in a row of dragged knuckles.

He parked under a buckled awning where shade offered itself to anyone with sense. His phone said No Service in the tone of a clerk closing a window. He could go inside and ask for directions. He could get coffee that didn’t taste like the inside of his thermos cap. He could look wrong and keep going.

The bell on the diner door belonged to an era that liked bells and order. It rang and the air inside met him at the threshold: cool, and sugared with something fried earlier. The floor was checkerboard gone to dust; the counter was stainless that had learned patience. A jukebox in the corner wore a cloth cover like a shy party guest. A single ceiling fan kept time with its own private song.

There was one other customer—a man at the far end in a denim jacket too warm for the heat, his hat pulled low, hands folded on the counter the way people fold them at wakes. He didn’t look up. The waitress did. She had the attention a good short-order place requires: eyes that found you and forgave you in one pass. Brown hair pulled back in a bandana. Nametag that said MARLA in a font that used to be proud.

“Anywhere you like,” she said. “Coffee?”

“Please,” Ren said, because here that word got you taken seriously.

She poured before he’d chosen a stool, set the cup where his hand already knew it would be, slid creamer across without being asked. He could smell the roast, a notch better than respectable. He took a sip and let the heat remind him what he was made of.

“Headed east?” she asked, more like a kindness than a question.

“That’s the idea,” he said. “Or it was. My map thinks the road exists. The road thinks otherwise.”

“That’s the desert for you. People draw lines where there aren’t any.” She glanced at his shirt—plain work tee, dark with a logo long ago washed out—and then at his keys, the way people read each other’s lives. “Delivery?”

“Yeah.”

“Big city today?”

“Started there.”

“Ends here, for a bit,” she said, like she knew a thing about how time worked.

On the wall behind the counter hung a row of framed black-and-white photographs: the town when new, a parade of trucks that had believed in this place, a softball team with faces you could still recognize in the bones of the men who might come in later. Above them, a clock that ran but didn’t care what hour it said out loud.

Ren took another drink. The coffee was honest. He let his shoulders down a notch.

“Kitchen’s slow on purpose,” Marla said, eyes moving toward the pass where no ticket dangled. “You want eggs, you’ll get eggs. Might just be later than you think.”

“Coffee’s good.”

“We’re proud of it,” she said, and she was. “You from the valley?”

“West side.”

“Long haul for a Wednesday.”

He nodded, then tapped the tube in his mind where it sat behind his seat. The label’s address had been twenty minutes outside his intended loop before the reroute. Now, with the signal dead and the road turned into a story people told about mistakes, he couldn’t swear where he was relative to anything.

“You got a paper map?” she asked as if she’d plucked the thought from his pocket.

“In the glovebox.” He grinned. “Like it’s 1999.”

“Nothing wrong with old tools,” she said, and then, because some people are careful with the next thing they say, she added, “You’ll want to take Hampton Wash to 23X and skirt the feeds. The main crossing won’t hold weight this week.”

Ren blinked. He hadn’t told her which crossing the app had promised him. He hadn’t told her anything that would make sense of words like feeds.

“You get a lot of lost drivers in here?” he asked.

“Enough,” she said. “Some aren’t lost. They just don’t know it yet.”

The man in denim cleared his throat without moving his head, like he’d agreed with the sentiment and wanted to be counted. He laid a few crumpled bills on the counter, left his coffee half-drunk, and went out without the bell ringing. Ren watched the door fail to open for him, somehow.

“Pie?” Marla asked, and the question was almost a lifeline.

“Sure,” he said, because you don’t refuse the desert when it offers you something sweet.

She set a cherry wedge in front of him that looked like it remembered July. He ate and felt human in the way sugar makes you remember your best self.

He reached into his pocket for the manifest out of habit—the record, the line items, the annotation space where certainty goes to live in ink—and paused because the paper he touched wasn’t there. He’d left the clipboard in the van. He lifted his hand, then let it drop. The tube weighed on his mind like a word he couldn’t put down.

Marla wiped a clean counter for the pleasure of it and said, “You can leave it here if you want. Safer than the road between where you are and where you think you’re going.”

“Leave what?” Ren asked, but softly, like he was afraid to wake something.

“The tube,” she said, and smiled because the kindness had finally shown its real face. “Behind the jukebox is where we keep them when we’re keeping them. Folks come through. Folks collect. The room knows how to hold a thing.”

Ren didn’t answer for a beat. The jukebox’s cloth looked heavier now, like it could hide history. He pictured the metal end caps of the cylinder catching that same neon light, the red script making a checkerboard on both their surfaces. He pictured a row of other tubes under there, each with a name, each with a story about a road that turned right when a map had said left.

“How—” he started, and then adjusted the sentence. “Why would anyone…?”

“Because the wash eats crossings without asking. Because your phone won’t like the next ten miles. Because sometimes it isn’t your turn to deliver what you’re carrying, Ren.”

His name landed on the counter like a coin. Not sir, not buddy, not nothing. Ren. Not on his shirt. Not on a card he’d handed over. Just there, with the cherry pie and the coffee that didn’t cool.

He felt his shoulders square themselves again, not from affront, but from that other thing—alertness. He placed his hands flat on either side of the cup and considered the ways a person could know a person: records, rumor, the way men at docks do, the way dispatchers say your name so often it changes shape. He thought of the crate from the night before and the tapping that had stopped when he’d wanted it most to continue. He thought of patterns that form when you pretend not to see them.

“How do you know my name?” he asked, and she met his eyes without blinking.

“We get the radio, same as anyone,” she said, and he believed the first half but not the last. “And some names carry more than others.”

“That’s not an answer.”

“It’s the one I have,” she said, not apologizing.

He let silence sit between them a moment. People imagine silence as an empty plate; it’s a table crowded with things you haven’t dared to name.

“What am I delivering?” he asked. He didn’t mean the tube. He meant the kind of work that creeps up behind the work you think you’re doing.

Marla laid the rag across her shoulder like a bartender in a movie and nodded at the window, where the desert did its best impression of forever. “Sometimes it’s only a message,” she said. “Sometimes a correction. Today?” She tipped her chin toward the jukebox. “Today it’s a set of lines. Lines that tell someone where to dig and where not to. Where water once thought about living. Where it might think about it again.”

Plans, then. Survey lines. The label had been a name and a road. He could guess a company, a ranch, a development that would turn emptiness into patterned emptiness. He pictured the tube tucked behind the jukebox with other futures rolled tight.

“Why here?” he asked.

She smiled like the question had walked in earlier and ordered lunch. “Because people find this place by accident. Which makes it the only place they all have in common.”

He laughed without meaning to, the way you laugh at a map that finally admits it’s a mirror.

“You can leave it,” she said again. “We’ll see it where it needs to go. Or you can take the wash and test the crossing and maybe you make it, and maybe you don’t. It’s not my van.”

Ren stared at the coffee. He tried to imagine explaining to dispatch that he’d left a time-sensitive delivery in a diner behind a jukebox because a woman whose name he had only because a tag told him so had told him she knew his. He imagined the look on the dockman’s face when he turned the tube back in like it was on loan. He imagined the road ahead as both question and answer and neither.

He stood, fished for bills, left too many because some places deserve a tip for existing. He nodded to the jukebox, to the idea of it, and to the room that could hold things.

When he reached the door, he turned back. “If I leave it,” he said, “how will they know…?”

Marla set the pot down, came forward, and lifted the corner of the cloth with two fingers. Beneath, a row of tubes slept like tame animals. Each end cap carried a strip of tape with tidy handwriting. QUINTERO SURVEY, VALENCIA MUNICIPAL, B. RILEY—WELL, HOLLAND. Space for one more.

“The room knows,” she said. “So do we.”

“And if I take it?”

“You’ll still end up where you’re supposed to,” she said. “It just might take more out of you.”

He put his hand on the door and let the bell’s thought of sound travel a few inches into the street. The heat waited. The van waited. The road waited, too, pretending not to.

He didn’t move.

Marla’s voice arrived like the coffee had: right where he was about to be. Gentle, certain. “Refill before you go, Ren?” she asked, and then, soft as if the names of things weighed more when you spoke them indoors, “And leave the tube behind the jukebox.”

Leave a Reply